Now isn’t this juxtaposition just rich? Erik Prince’s self-serving book on the left and Scahill’s–who rose to fame by vilifying Prince, which assuredly set the stage for him getting 2nd book deal resulting in Dirty Wars–on the right. Wonder if the store employees thought this was a funny contrast. I certainly did.

New York- After being gone from the U.S. for a long time one of the weird readjustments I often make is coming back to book shops (the ‘brick and mortar’ ones still standing anyway) is the avalanche of new books from the people whose careers seem to be quickly surpassing mine at least in terms of fame, chat show appearances and cold hard cash. While others were skillfully negotiating book deals I’m either running around some place forsaken by god chasing down some obscure story in South Ossetia or Kirkuk that few in the outside world give a damn about.

More power to the guys and gals getting said book deals. I hope to join them in the near term. But something that has spoilt my usually pleasurable experience is having spent two years rigorously editing a behind-a-paywall publication for a D.C. think thank. Now I can’t seem to look at any new history or current affairs tale I happen upon and find some kind of error. And I’m not looking for errors per se, I’m leafing through the new release non-fiction shelves for enjoyment and opening them in the middle and reading chapters at random totally out of order. But what to do? Last year I found numerous, glaring factual errors in the very beginning of Kurt Eichenwald’s 500 Days: Secrets and Lies in the Terror Wars. When I contacted who seemed like the relevant person at Touchstone Books, my email was of course ignored. I was literally simply trying to help for the sake of the historical record, not make a famous author look foolish.

The other day I picked up The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide about a serious dreadful ‘realist’ Nixonian policy decisions during Bangladesh/East Pakistan’s war of independence from Pakistan in 1971. I open it to a random page and it is discussing the Maoist response to the deadly crisis in eastern South Asia during that awful period. It describes PLA troop movements near “Sikkim, a small Indian state nestled in the Himalayas.” Now I am certainly no savant on Indian history but I do enjoy 20th century South Asian history as a bit of a hobby a red flag rose. Sikkim was a legally independent state that did not accede to the Indian union until 1975.

To be fair to the author, Sikkim as it existed as a post-Raj monarchy was a tribute state to Nehru’s India which depended on India for its external defense (i.e. from Maoist China) as it sat wedged between the independent kingdoms of Nepal and Bhutan. But during Bangladesh’s national liberation, Sikkim was most definitely not a constituent state of the Indian republic, not for four more years. I kind of wonder if arriviste so-called ‘millenials’ are editing today’s volumes because they seem to be rife with these kinds of discrepancies, however minor seeming. Some years ago I stumbled upon a coffee table book about independent Sikkim that pre-dated 1975 which depicted the life of Hope Cooke, a Manhattan socialite who married the monarch of Sikkim and whose life was once followed by the American press with some fascination.

None of this is to say that The Blood Telegram is no less of an important work of history. The war in Bangladesh has constant reverberations to this date, most recently owing to the war crimes tribunals in Dhaka.

The struggle for Bangladesh, which came to the attention of a good many in the West with George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh perhaps, has had global consequences. Dhaka just now is going through a bout of painful war crimes trials that is felt all the way in Queens where the migrant diaspora is torn between secularist ‘freedom fighters’ and pro-Pakistan Islamists. Bangladesh is the world’s most densely populated nation-state hemorrhaging economic migrants as if it were a bleeding organ atop the bay of Bengal. Bangladeshis have followed the Pakistani migrant model all around the world but in what seem like greater numbers. From Los Angeles to New York to Barcelona small businesses that were once ubiquitously Pakistani are increasingly Bangladeshi.

New York magazine cited a statistic that the migration rate of Bangladeshis to New York City increased 178% under the mayoralty of Michael Bloomberg, the highest of any single ethno-linguistic group in the world to New York. The events described in The Blood Telegram roils the migrants whose Bangla-laguage media obsesses over the “battle of the begums” between the alternating, warring, tiresome female prime ministers Khaleda Zia and Sheikha Hasina.

Next I picked up The Way of the Knife: The CIA, a Secret Army, and a War at the Ends of the Earth by Pulitzer winner Mark Mazzetti, of the NYT’s Washington bureau. I’d seen about this book when it came out but hadn’t been able to leaf through it as it’s not being heavily promoted in Tbilisi or Santorini.

One morning in March 2010 I awoke to find that Mazzetti and his then colleague Dexter Filkins had written a front page story titled “Contractors Tied to Effort to Track and Kill Militants” on a couple of characters called Michael Furlong ( whom I’d never heard of until that moment) and the rather notorious Duane “Dewey” Clarridge or Iran-Contra fame. The second echelon of players in that story were an “iconoclastic Canadian writer” named Robert Young Pelton and a “suave former CNN executive” named Eason Jordan. This article forms the central arc of The Way of the Knife although of course my, I suppose, minor role in the view of Mazzetti is never mentioned.

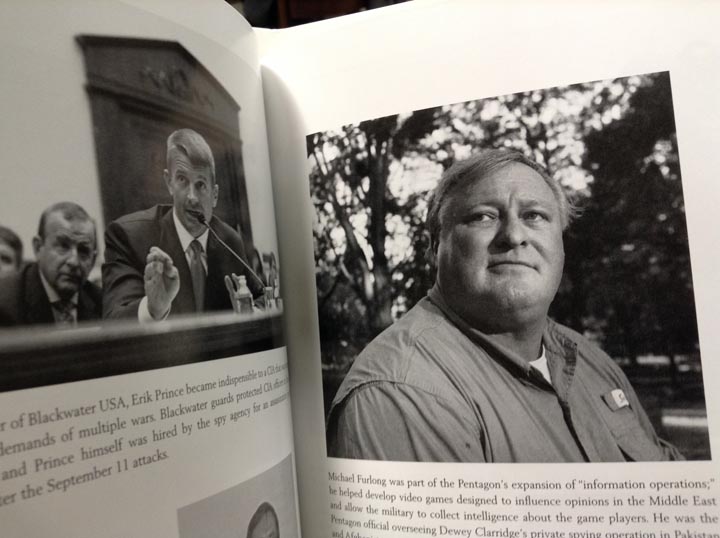

Furlong pictured in Mazzetti’s book. Pelton and Jordan had never mentioned this clown to me when Afpax Insider was being conceived. Perhaps it was all on a need to know basis. Seeing as they never cleared the air to my satisfaction, I’ll be left to my assumptions.

I haven’t heard from a word Pelton since this weird scenario 3 1/2 years ago. He and Jordan gave me no warning that the story was coming out–which they surely must have known was coming. Then Jordan asked to me retract my statements on the affair made to Mother Jones in an article called “The Pentagon’s Stringers” after an enterprising MJ reporter in D.C. had somehow (?) gotten my landline which I don’t have listed. When I saw that a photo I had taken in Kabul for Pelton and Jordan’s site appeared in the NYT in a screen grab used to illustrate the article, I felt I’d essentially been thrown under the proverbial bus. I contacted Filkins after the article hit and he seemed to not have the faintest clue who I was nor did he appear particularly interested in communicating with me.

Sort of weird considering my name is big letters on this side of the image in his article. I’d sat next to Filkins at Dr. Abdullah’s house the previous year during the 2009 Afghan elections but I wouldn’t expect someone of his caliber to put two and two together as I’m someone deep in the journo underground in relative terms. Obviously it wouldn’t have occurred to Mazzetti to contact me in doing the research for his book as he likely a) would never have heard of me or b) I’m not iconoclastic. I think Pelton and Jordan set their sights on Somalia after this whole ordeal and Pelton is still a friend of a couple of friends of mine to this very day but he hasn’t contacted me since the scandal. And that’s fine with me I suppose. I never bothered to hold a grudge, I just moved on. Then the Arab Spring happened and I haven’t made it back to “AfPak” since.

Now here is where I take an issue. There is an earlier chapter in the book where Mazzetti profiles the life of Nek Mohammed. At a cursory glance, he states that Nek Mohammed [Wazir] “found his calling in 1993, and was recruited to fight alongside the Afghan Taliban against Ahmad Shah Massood’s Northern Alliance in the ciivl war then raging in Afghanistan.” It is common knowledge that the Taliban was formed in in Kandahar in 1994, not 1993. Nek Mohammed–who was killed in an American drone strike in June 2004— had fought alongside them in 2001 as had other Wazir tribesmen. A recent work put out by Peter Bergen and Katherine Tiedeman also says Nek joined the Taliban in 1993. While it could perhaps be argued the Taliban began to coalesce in 1993 the movement was not a known entity of any note until 1994.

Now here is where I take an issue. There is an earlier chapter in the book where Mazzetti profiles the life of Nek Mohammed. At a cursory glance, he states that Nek Mohammed [Wazir] “found his calling in 1993, and was recruited to fight alongside the Afghan Taliban against Ahmad Shah Massood’s Northern Alliance in the ciivl war then raging in Afghanistan.” It is common knowledge that the Taliban was formed in in Kandahar in 1994, not 1993. Nek Mohammed–who was killed in an American drone strike in June 2004— had fought alongside them in 2001 as had other Wazir tribesmen. A recent work put out by Peter Bergen and Katherine Tiedeman also says Nek joined the Taliban in 1993. While it could perhaps be argued the Taliban began to coalesce in 1993 the movement was not a known entity of any note until 1994.

When I was reading Ahmed Rashid’s seminal Taliban: Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia at Saeed Book Bank in Peshawar (a great book shop by the way) in 2000, he described the Taliban has having “emerged in 1994” replete with a chapter titled “Kandahar 1994: The Origins of the Taliban.”

Further down the same page, he talks of “Chechen al-Qaeda fighters” who fled to Pakistan at the outset of Operation Enduring Freedom. While impossible to entirely disprove this meme, this is a completely unsubstantiated self-replicating notion propagated for years by Russian authorities in their brutal war against Chechen separatist in the North Caucasus for which there is not a shred of empirical evidence.

In Chechnya in 2001, the rebels were still largely an ethnic national liberation movement who used mostly Sufi Islam of the Qadiriyya order (as well as the Naqshabanidiyya order) as a spiritual motivational factor in the fight and in order to emphasize religious difference with their Orthodox Christian Slavic Russian enemies (on the federal forces level) on the battlefield. Those in the Lubyanka in Moscow worked very hard to convince the world they were fighting a bunch of maniacal “vahabbis” in a Eurasian war on terror rather than continuing a genocidal Czarist and Stalinist policy of crushing the rebellious peoples of the Caucasus. Washington and hence its proxies in Pakistan then bought into a bunch of this nonsense hook, line, and sinker. (The Syria situation will be discussed at length in my forthcoming report).

When Mullah Mohammed Omar’s Taliban regime was completely isolated after failing to gain international recognition, out of spite or desperation it belatedly decided in the name of transnational Islamist solidarity to recognize the independence of the self-styled Chechen Republic of Ichkeria-itself a moot action seeing as the Taliban were not recognized as the rightful rulers of Kabul except by Islamabad, Abu Dhabi and Riyadh.In mid-January 2000, the Taliban came to an agreement with envoys of Aslan Maskhadov, the late Chechen independence leader, to open a Chechen diplomatic outpost in war ravaged Kabul. A couple of Chechen rebel diplomats does not a giant wave of Chechens fleeing into Pakistan after 9/11 and ensuing Daisy Cutters make.

This does not equate to a grand strategic partnership between Chechen fighters and al-Qaeda 1.0. Furthermore, Pakistani security forces at that time would not likely have been able to tell the difference between salafi Russophone lingua franca jihadis. Neither would members of the CIA in working partnership with the ISI in all probability. Furthermore when I interviewed foreign fighters after the fall of Mazar-i-Sharif, they were almost all Deobandi Pashtun and Punjabi men from Pakistan, not a Caucasian Sufi among them.

All that being said, or rather, written, The Way of the Knife is a thoroughly entertaining read for those interested in high stakes intelligence genre that will have real world repercussions well into the next generation that will inherit these awful policies borne of the Bush administration and amplified by the Obama administration.

I love books and I love book shops…but come on publishers, let’s get some more older, more experienced editors out there! Maybe these mistakes or whatever you want to call them are in no way the fault of the relevant authors but the fact checking must be more rigorous. Just my opinion though.