©2019 Derek Henry Flood

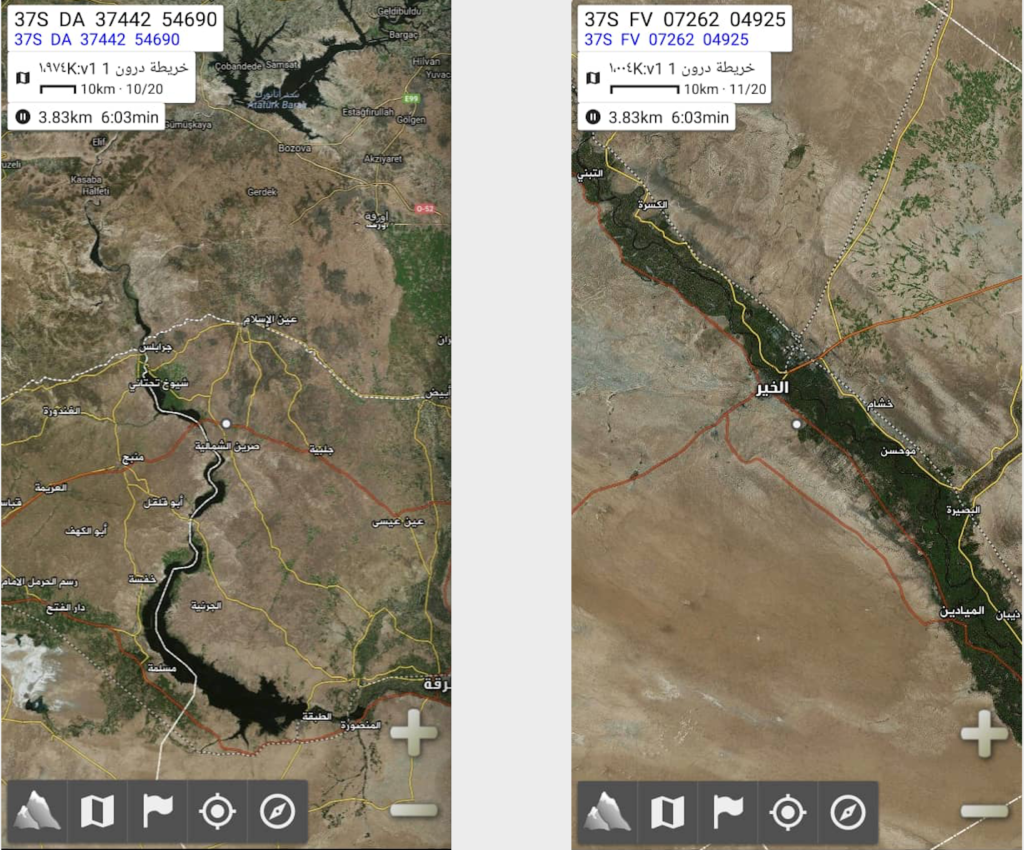

New York- A couple of months ago I was riding in a van along a rough hewn piste in Deir ez-Zor governorate’s al-Jazeera region east of the Euphrates river when i was shown a map app that IS had used against its enemies be they an-Nizam (“regime” or “ruler” meaning the al-Assad government), the Quwaat Suria al-Dimuqratia (ie the SDF), Jabhat al-Nusra, or local tribes. From this almost chance technological encounter, I have a report for Jane’s Terrorism and Insurgency Centre in the UK titled “Captured Islamic State map files underscore technological capabilities and priorities for state building.”

Though IS certainly did not architect the app itself, that was done by mysterious, apparently French developers calling themselves Pysberia.net, they innovated well within its boundaries in order to crush their battlefield opponents and thus gain more territory befitting their expansionist worldview. Despite that I’ve been covering the IS beat since it was still ISI and largely confined to central and northern Iraq, this discovery made me more viscerally cognizant of the group’s tech capabilities in a first-hand sense.

My escort from the Deir ez-Zor Military Council was using the captured map files to help guide me safely back from their barracks in al-Kasrah near the river to a road leading up to al-Hasakah toward relative security. This was toward the end of the battle of al-Baghouz further south and IS guerrilla attacks were focused far more on busier, sealed roads than out in the bush. In essence we were doing our best to circumvent a possible insurgent attack by using the maps and routes of the insurgents themselves dating to their proto state-building efforts.

Neither the SDF constituent militias nor an-Nizam have such savvy tech skills or hyper adaptability even in the wake of IS’s territorial collpase. Part of the war in Syria, and Iraq for that matter, is one armed actor constantly playing catchup with the next in terms of technological exploitation and capability. Much as I hate to admit, IS was seemingly light years ahead during the peak khilifah (caliphate) period than any other nearby armed actor. The SDF, Iraqi security forces and others had always been at least two steps behind on the tech front. But as the khilfah steadily shrank from late 2016 onward with concerted effort of external force air strikes, ground forces were able to vacuum up heaps of intelligence that lay in the wake of dead or retreating militants. Reading the work of colleagues or competitors on a topic like this isn’t quite the same as experiencing this phenomenon on one’s own. I had to confront how complex the workings were of an organisation I loathe immensely was. I then put immense effort into unpacking this utterly sophisticated intelligence for which there was a significant learning curve as someone who doesn’t work in tech and is often in war zones with gear that’s at least 3 years old. These globalist génocidaires really did have the upper hand in this region for a while and that is not an easy thing to accept on the most base ethnical level.

Local forces gathered information on how exactly IS governed. As they did, the picture became clearer on just how they enforced a writ that was simultaneously medievally brutal and hi-tech in the most 21st century sense. From Silicon Valley to Guangdong province, technology companies often market themselves as rather benign entities that either will help to further democratise societies (the former) or keep consumers entertained in undemocratic states that eschew the most basic freedoms (the latter). But as my work demonstrates, software and hardware is only as innocent as the intentions of its users. So this ostensibly French-developed app meant to guide hikers through, say, parts of the Pyrenees or the Rockies where mobile service is spotty or scant, was adapted to help guide suicide vehicle bombers toward their targets on either side of the Sykes-Picot line they sought to dissolve. It also says something about the potential for cruelty in our collective human psyche. Breakthroughs in coding and computing can enable a genocidal cult just as much as they could accelerate positive change in traditionally underserved, marginalised communities.

Just as there is no unified approach to combatting IS on either side of the Syria-Iraq border between the SDF and the ISF-Hashd al-Shaabi which have vastly different local geopolitical aims in their role as anti-IS war fighting groups, there is no commonly accepted agenda amongst the world’s inflated tech industry titans on how to balance free speech with the global spread of varying forms of political violence their platforms help inflame. I’m of course not suggesting technology is a cause but rather a conduit as violent acts become increasingly transnational from Syria to Iraq and from Australia to New Zealand.