A massive piece of art in Brooklyn's Williamsburg section celebrating Bradley Manning, the Army private who passed a massive United States government document trove onto the anti-secrecy site Wikileaks.org. Manning, currently in detention at Fort Leavenworth, disclosed information which today is classified as secret but will one day very likely simply be part of the collective historical record. Lessons from history are rarely if ever learned by government. Perhaps it is finally time to reexamine our methodology. The balance between state secrecy and open governance almost invariably tilts towards further secrecy. Yesterday's release of yet more Nixon tapes and testimony-more than 17 years after his death-reinforce this idea. ©2011 Derek Henry Flood

New York- I saw one of these living, contrasting images on the subway here the other day where I wonder if I am the only one observant or nosey enough to notice these things. An older man boarded the train donning a black leather vest with a green outline of Viet Nam divided rather starkly between North and South by a US Marine Corps rank insignia. I was born the year Viet Nam’s indigenous war ended and two years after it effectively ended for the United States. The political fervor of the Johnson and early Nixon era, where fighting Communism was deemed as an existential fight for America’s values at home as well as the biggest external challenge to American supremacy in the Pacific and Eurasian rimland realms, defined the imagery of my upbringing. We were all “All Along the Watchtower.” Standing next to this man was a smartly dressed, city chic thirty-ish woman reading a fresh paperback.

Curious to know what others are reading to pass the commute time, I glanced over her shoulder to see who the author was and noticed it was a novel by a Vietnamese writer called Aimee Phan. The book was titled The Reeducation of Cherry Truong, a post-Viet Nam war odyssey of sorts. Looking it up on Amazon when I got home, I saw it won’t be out for some time, meaning the reader on the subway either worked for the publisher or a media outlet provided an advance copy to review the book. So here was a man representing the blood, death, and tears of a futile war with an invisible, unreachable goal and next to him a confident post-feminist woman born after his war’s end reviewing a book putting the war more firmly in history rather than the still very present tense of the vest wearer. Both of them appeared to stand oblivious to one another.

Sure perhaps we can revise our view and say that the war was either to buffer the vehemently anti-Communist but far from democratic South Vietnamese state or overturn its Communist peer competitor in the North. But in the context of the era, the American public was often extolled of the virtue of defeating such an evil ideology. That must not be forgotten. In 30 years, will there be a young person reviewing a book-in whatever form books will be in 30 years (assuming they still exist)-written by a second generation Iraqi-American author putting that war in the appropriate perspective with a grizzled yet proud Iraqi Freedom veteran nearby looking off the other direction?

Militaries and sometimes insurgencies can be defeated on the battlefield with overwhelming force and a scorched earth campaigns respectively (think Operation Desert Storm for the former and the Filipino insurgency in Luzon during the Spanish-American war for the latter). Though it may be possible to let the gun barrels cool down once both sides have exhausted themselves through the implementation of physical and psychological violence, it is impossible to kill ideas. Ideas can only be bested by more innovative, successful ideas, not columns of tanks and harsh secrecy laws. This is the eternal struggle between the short and long views of the intellectually ill-equipped men who describe themselves as “history’s actors.”

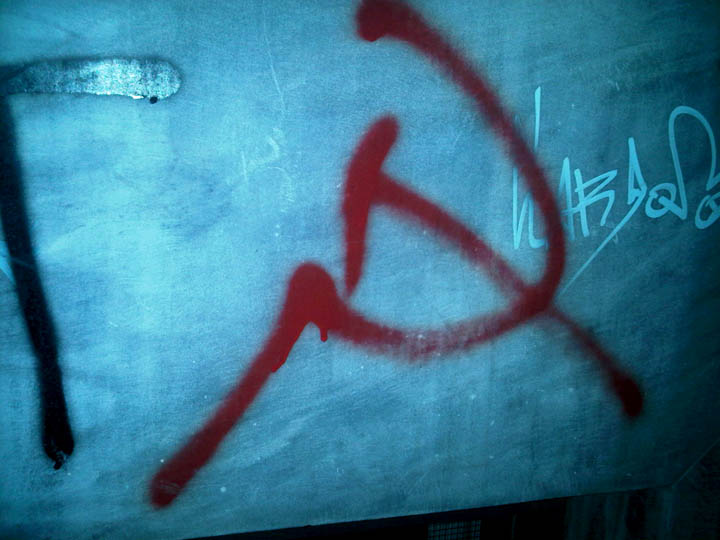

Tens of thousands of Americans died fighting to contain the spread of Asian Communism in the Korean and Viet Nam wars. Countless Americans served in Europe during the Cold War to stem the westward geographic creep of Soviet Communism. Today in troubled European cities like Athens (pictured here) rife with economic disquiet, the symbols of Marxism and Leninsim have failed to disappear. One has to ask, what was it all for? And was it all really such a success? Or did American triumphalism confuse Soviet and Warsaw Pact economic state collapse with the death of an ideology? Did America provide a security umbrella in Europe for decades only to allow for the freedom to espouse Communist ideology in the EU's economically devastated "olive belt" countries? ©2011 Derek Henry Flood