New York-A piece came out in the New York Times Business section titled “An Arrest in Canada Casts a Shadow on a New York Times Star, and The Times” after I spoke Ben Smith, the paper’s media columnist and former Editor-in-Chief of Buzzfeed News, about my experiences working furtively on a controversial podcast about 2 1/2 years ago.

At the time I was in the troubled city of Manbij in Syria’s Aleppo Governorate. I had just wrapped up a reporting project for a client on the challenges faced by the Manbij Military Council, the local constituent militia of the then American-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Manbij was a hotbed of intrigue partly purely because of its wartime geography in that it was west of the mighty al-Furat, or Euphrates River, and the presence of the SDF there, along with an American base outside the city was unacceptable to the seemingly constant Turkish bellicosity emanating out of Anatolia just to the north. Ankara viewed the presence of an SDF outfit in proximity to both the local Arab proxy fighters like Ahrar al-Sham it backed along with proper elements of the Turkish armed forces as a sort of sitting provocation waiting to explode.

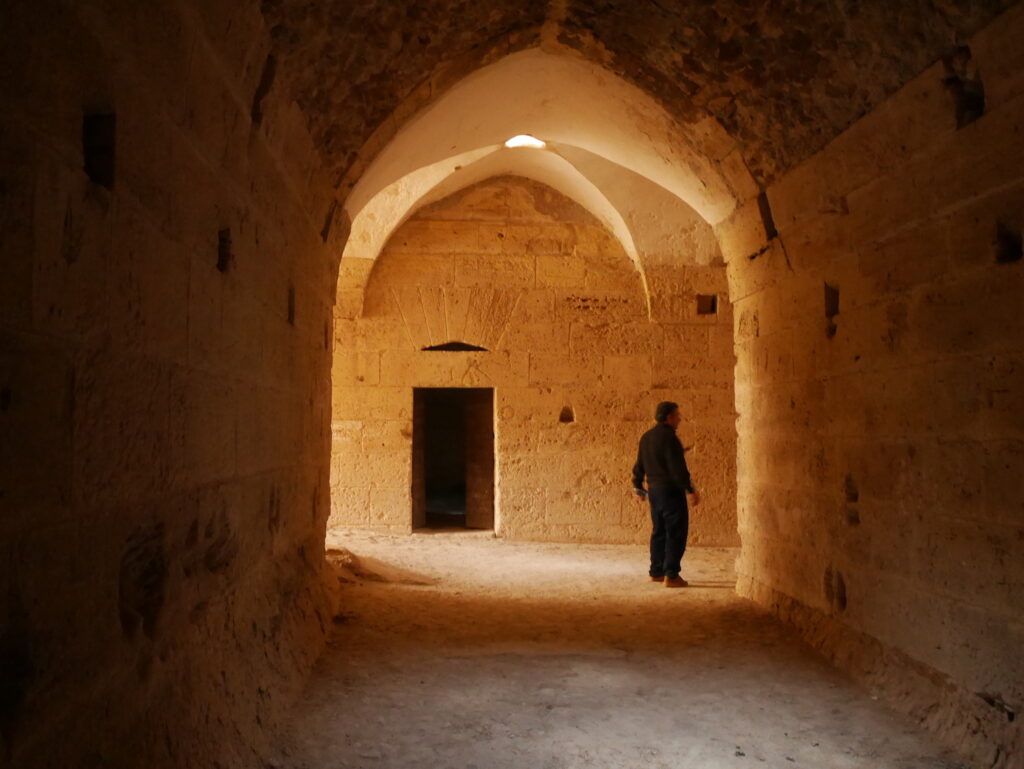

Part of why I was still in Manbij was because of my fascination with the historic extremities of Alexandrian-era Greece. Manbij was a trading settlement in the Hellenic era and even used the drachma as its currency. Locals I had met were proud of their city’s Greek origins and with my own origins in the Levant belonging to archaeology rather than modern warfare I was enthralled and stuck around for a few extra days.

While I was in Manbij, the city was a transit point for members of the Yenkineyen Parastina Gel (YPG), the People’s Protection Units and Yekineyen Parastina Jin (YPJ), the Women’s Protection Units, who were traveling to Efrin (alt. Afrin) district on the other side of the governorate to wage a resistance campaign against Turkish forces and anti-Kurdish salafist Syrian fighting groups in their horrendous Operation Olive Branch campaign. So in essence a lot was going on there at the time.

But when I would reach out to news outlets about an incredible story I had about a local archaeologist who had protected a network of ancient underground churches, they would tell me they had a policy of not working with freelancers moving around Syria. Hell, this even applied after I was back in Europe and trying to pitch a completed story from Syria despite being long gone. The Washington Post, BBC, and others told me no deal. Thus I was surprised to get the job at the NYT in that context and happy at the prospect of having another project even though it seemed likely impossible. What I wanted to do was work with local sources and have them tell me about their experiences living under the hisbah morality police, and IS in general. I thought I could add colour to the podcast and give it an on the ground Manbiji feel. But alas the podcast was only interested in things that supported the preconceived narrative. My input was not desired and nobody there cared who I was or anything about my past accomplishments.

©2018 Derek Henry Flood

I had a bad feeling about the project from the get go. I was in a Whatsapp group text about the project and I immediately googled each person involved, followed them on Twitter, and pinged their Linkedin profiles with a view. I wanted to put names to faces, to know who I was working with. I’m an intensely curious person who has no chill as they say. Laid back people don’t go all the way to Manbij and ar-Raqqa in the first place. The things I do are based on drive. None of the people in the text group dignified me with a follow back on Twitter or were curious enough to look at my Linkedin. How the hell do you get a job at the NYT by being so incurious? Isn’t that the whole point of journalism? I can’t understand that. You’ve got a guy running around on the ground in Syria and you aren’t remotely interested in who this person is? If you don’t work in media, what I’m describing will sound petty and insecure. If you do work in the industry, you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about. I believe in collaboration and mutual respect and this situation felt purely transactional at best. Yet I still held out a modicum of hope.

But then the podcast came out and I wasn’t even told about it, Not tagged in a tweet, nothing. On top of that my name was incorrectly attributed in the visual credits of the project. All they had to do was copy and past my name from my Twitter or Linkedin profile but oh they couldn’t because they likely never even googled me. So I was listed as “Derek Flood” rather than Derek Henry Flood. That seems like a minor difference that’s of no import until you realise that “Derek Flood is an evangelical Christian writer with a sizable internet presence that I cannot be confused with, especially considering I work in hostage-prone environments. This wouldn’t have happened if any had bothered to reach out to me and ask, “Yo BTDubs how do you want your name to appear?” I had previously had a problem with the Huffington Post when the Protestant Derek Flood started writing for them years after I did and they confused all our avatars and my face was all over stories about the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth and his mug was on my stories of the Rohingya genocide in Burma. I finally got it corrected it but still. Dangerously #awkward.

So my mind began racing about this rather obscure request to begin research on a podcast for a major media outlet. I first began with asking the people at the Manbij Civil Council that I’d befriended about their memories of life under IS rule and if they could remember the exact locations of IS administrative structures. which I thought could be useful for the podcast. I was only told the kunya, nom de guerre, of the muhajir (“emigrant”) fighter/recruit/volunteer as “Abu Huzayfah.” I was provided with practically no other supporting information on the topic I was meant to research in the city’s dusty warrens. So I was meant to ask ordinary Manbij’een about a foreign fighter I was supposed to know almost nothing about. This to me seemed like such an untenable idea. How was I to ask informed questions on a shady figure I had no information about? Thankfully because Google I put together that he was from the Pakistani diaspora in the Mississauga area of Ontario. Having lived in a Muslim South Asian area of New York City, from time to time I spot Ontario licence plates on the street and upon closer inspection they just about always have a dealer sticker from Mississauga, home to to its bustling Desi community. So I figured this young guy is likely from Muhajir culture (meaning not indigenous to the the provinces that make up what is now present-day Pakistan, ) which were/are the Urdu-speaking Indians from, say, Uttar Pradesh, that migrated from UP to, say, Karachi, the then capital of the nascent nation-state, during Partition in the summer of 1947 before moving Ontario because, well, Commonwealth.

Part of the problem with this premise of researching this Sunni Desi kid whose actually name I was not privy to (turns out it’s Shehroze Chaudhry from Burlington) is that people in Manbij I spoke to were far more eager to talk about foreign fighters from more far-flung parts of the Arabic-speaking world than some third culture kid with salafi-jihadi fantasies and a Telegram account. Despite these obstacles I really put my effort into trying to help the podcast. I just felt the idea behind the podcast being centred upon a singular obscure character was far too narrow in scope but I’m neither famous nor a decision maker in an office tower in midtown Manhattan so I decided to see what I could figure out. The problem was bascially right away that Mustafa Bali–the SDF’s essential media wrangler– got wind of my doings down at his office in Ain Issa in ar-Raqqa Governorate and summoned me and my friend/driver/body man down there for a stern talking to.

After crossing the Euphrates, we passed by the notorious Lafarge cement plant visible from the M4 motorway that was charged in a Paris court for crimes against humanity and financing terrorism when it paid off salafi-jihadi war-fighting groups to protect its business interests. The French industrial giant (since having become the Franco-Swiss LafargeHolcim) was said to have thought that by keeping the plant open, they could cash in on a potential post-war reconstruction boom. Nearby I spotted American troops pulling into the protective Hesco bastions that are so common in Iraq and had made their way into the Syrian battlespace.

©2018 Derek Henry Flood

As we approached Ain Issa, we sped past the fetid IDP camp. The stench was absolutely overwhelming. Having been there when it was first being erected the previous year, it was hard to see that it was already having a sense of permanence. Once passed the camp, my apprehension skyrocketed as we approached the SDF media base in the town proper. Would they even know or care what a podcast was?

©2018 Derek Henry Flood

To give a little background, the SDF, the Asayish (internal “security”), and various bureaucratic organs of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) have a vastly complex paperwork system where as a foreign journo one must obtain what seem like an endless quest for what are known as permission papers to gain access further afield. The process was so exasperating and time wasting that the NYT’s Rod Nordland resorted to doing a story on the paper chase itself.

I made sure to not address Bali in English at all (which he claims he doesn’t speak but there are always rumours of him totally comprehending it while pretending not to) and proceeded to tell him of my doings in a whole Kermanji Kurdish script I had put together in my head on the drive down there. Spending tons of time with my driver friend (who I’m pointedly not naming for his own desired anonymity) I had managed to pick up a good bit of the Kermanji dialect by this point. It differs significantly from the Sorani dialect spoken in Iraq in that it weaves in a lot of Arabic terms whereas to me Sorani feels more closely related to actual Farsi in Iran from which Kurdish as whole is related. Syrian Kurds don’t maintain the same animosity toward Arabic as their Iraqi counterparts who had 20 more years experience on separating themselves from the rest of Iraq (1991 in Iraq vs 2011 in Syria). I told Bali of my assignment for the big rojname (“newspaper”) and he was not the least bit impressed by my name drop.

Mind you I only dropped said name once the conversation already was clearly a confrontation with a predetermined outcome. I, much less the NYT, was not going to win this one. Bali told my friend that I needed to leave Manbij straight away and it was on him to make sure I did such otherwise he’d be in trouble with the SDF hierarchy. That was one hell of an awkward drive back up to Manbij. I tried to make jokes to lighten the mood but wasn’t all the successful. Early the next morning I hurriedly left the Manbij Civil Council building with barely time to say goodbye to the friends I’d made over the weeks there and was driving to a minibus “garage” (parking lot with minibuses going all over the AANES-controlled parts of Syria) and waited for a silver Hyundai minibus to sell out every seat before we could head east to Qamishlo. The whole ordeal was weird and kind of depressing. I hated having to leave under duress after working to build all those relationships. But just like that it was over.

The danger however became verifiable when just two weeks after I left a UK and US solider were killed by an improvised explosive device inside the city. I then learned that barely a week after I left there was an assassination attempt against the affable MMC spokesman Shervan Darwish who had been so helpful to me during my time there. Thank god he survived. Without his kindness my work there would likely not have succeeded. You can’t accomplish anything in Syria without the help of your local contacts-cum-confidants and, as outsiders, they deserve our utmost respect and admiration. Heval (comrade) Shervan and I had endless cups of tea in his office discussing the nuances of the neo-Great Game taking place just beyond the grain silo complex where the MMC was headquartered. It was likely Turkish proxies or Turkish intelligence itself that tried to take him out. I’m glad they failed.

But I went back to the al-Soufaraa hotel on Qamishlo’s main street and checked back into my $7.50 USD/night room and made a plan to cross the Tigris back to KRG-controlled Iraq almost immediately. There’s an odd feeling leaving Syria because each time you cross from the Semalka border post to Peshabor on the Iraq side, you never know if you’ll be allowed by in owing to either the Byzantine bureaucracy permission paper system or the constant talk of the Iraqi federal government retaking the KRG-controlled border or the al-Assad regime taking over Semalka in a deal with the PYD. The entire situation is inherently unstable and no one can say how long this soft, informal border crossing will last. Then there are the tensions between the PYD and the KRG, namely the Barzani clan’s KDP that occasionally shut the border. There are no end of pitfalls in this zone.

Despite all of these things, I will never not love Bilad ash-Sham, the Levant, Greater Syria, the Eastern Mediterranean, Greco-Syria with its telltale traces of Hellenism in the east, AANES, however the region may be referred to or refer to itself. I’m far more interested in Phillip the Arab than Bashar al-Assad and always will be.