Wilmington, Washington D.C., & Charlottesville- Having early voted in NYC, I hit the road on election day to get a feel for what was going on in the rest of this vast country, well at least on the immediate eastern seaboard. My initial plan was to drive straight to the nation’s capitol to assess what was going on there in the aftermath of this most contentious voting period. While en route to D.C. I spontaneously decided to take a detour into Wilmington to see what, if anything, was going on related to the Biden campaign. I thought I might see a billboard, a flag, some yard signage. As I drove around the people-less night downtown of Delaware’s commercial capitol, all there seemed to be were gleaming bank buildings, one after another. But no sign of the Joseph R. Biden campaign, just plenty of visuals regarding much more local elections.

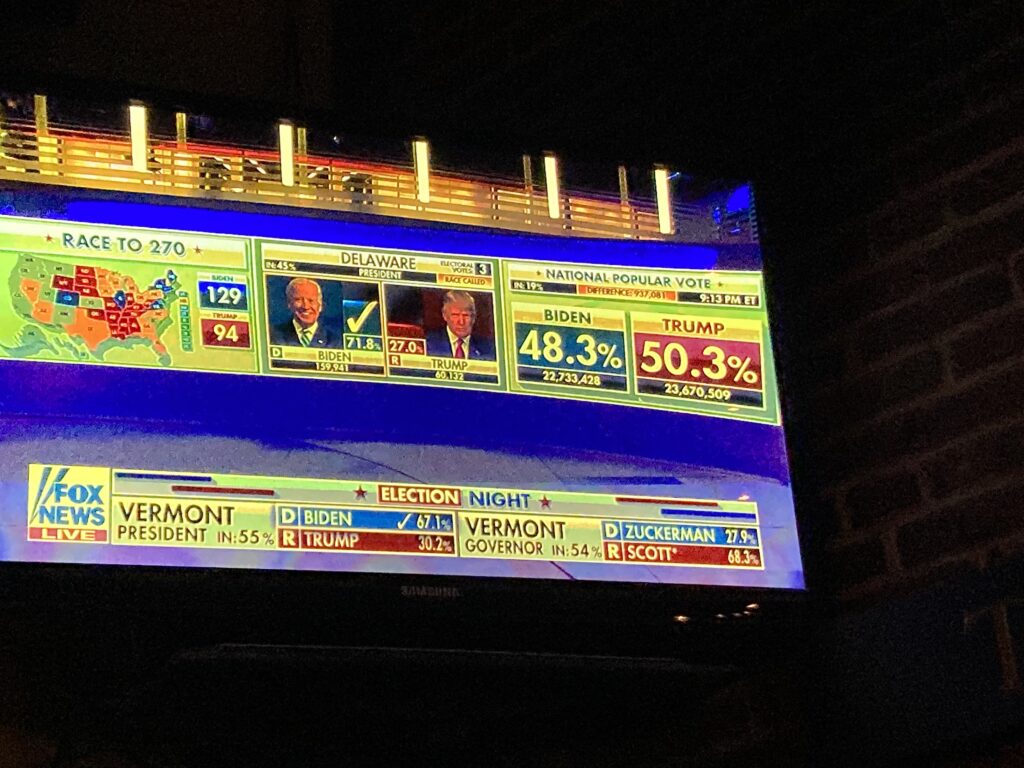

I expected a festive or maybe anxious atmosphere in Wilmington as election results tallies were announced in the obnoxiously blinding graphics of cable network news channels. Instead the city of banks and Biden felt deserted. So I popped into a local tavern called Dead Presidents replete with an ultra kitsch White House theme to get off the road and attempt to get a feel for what was going on at the height of an election in the midst of a deadly pandemic.

©2020 Derek Henry Flood

To say the number of televisions in this place was overwhelming would be an understatement. On the night of the 3rd, presidential politics was sport and this was the place to be. Deep as one could be in Biden country if it can be said such a place exists. For a Trump voter is commonly known as a ‘Trump supporter’ akin to die hard a Manchester United fan but I’d never heard of such a thing as a ‘Biden supporter’ even on election day. Biden voters in major coastal cities were sort of thought to be a disappointed cohort from the Bernie Sanders bloc who were left with no other choice. There were vague slogans appearing in sticker form in Brooklyn saying things like “vote him out” that didn’t acknowledge whatsoever who the democratic candidate even in fact was.

One of the televisions was tuned to the local news which showed a siren bathed convoy of none other than soon to be President-elect Biden racing toward the city’s Chase Bank stadium to give some sort of speech. I wasn’t entirely aware the candidate was present. I thought he would either be at his national campaign HQ in not all that far away Philadelphia or perhaps in Washington itself. Nope. He was home in the city of banks. I raced down toward the stadium just to see, well, of there was anything to see. Some visible form of excitement. A state trooper parked nearby tried to talk me out of getting any closer. He was not enthused in the slightest. I nodded and then didn’t listen to him, walking briskly to get close to the event. Biden was going to say something but nobody seemed sure what. I ended up in this strange fenced off parking area where European media were all assembled and instead of getting a glimpse at the candidate’s convoy or hearing a distant sound bite echoing across the stadium grounds, I was interviewed by a Swiss TV crew as the necessary American everyman who just happened to have snuck past dozens of Delaware policemen.

And that was the end of it. No sign of the future elderly leader of the United States. Just generators, foreign correspondents, and bright lights, small city.

The following day I headed down to Washington in the wake of what seemed to be a preliminary Biden victory. At the risk of being obvious, I was taken aback by not just how many big businesses were hunkered down in plywood but how many small businesses were gone for good. Despite the glorious weather, the mood was dark. To lift things up a bit I went for lunch at an Eritrean restaurant and chatted up the owner about her country which has had the same leader since its formal independence from Ethiopia in 1993. She knew a little something about a glowering man who refused to leave office.

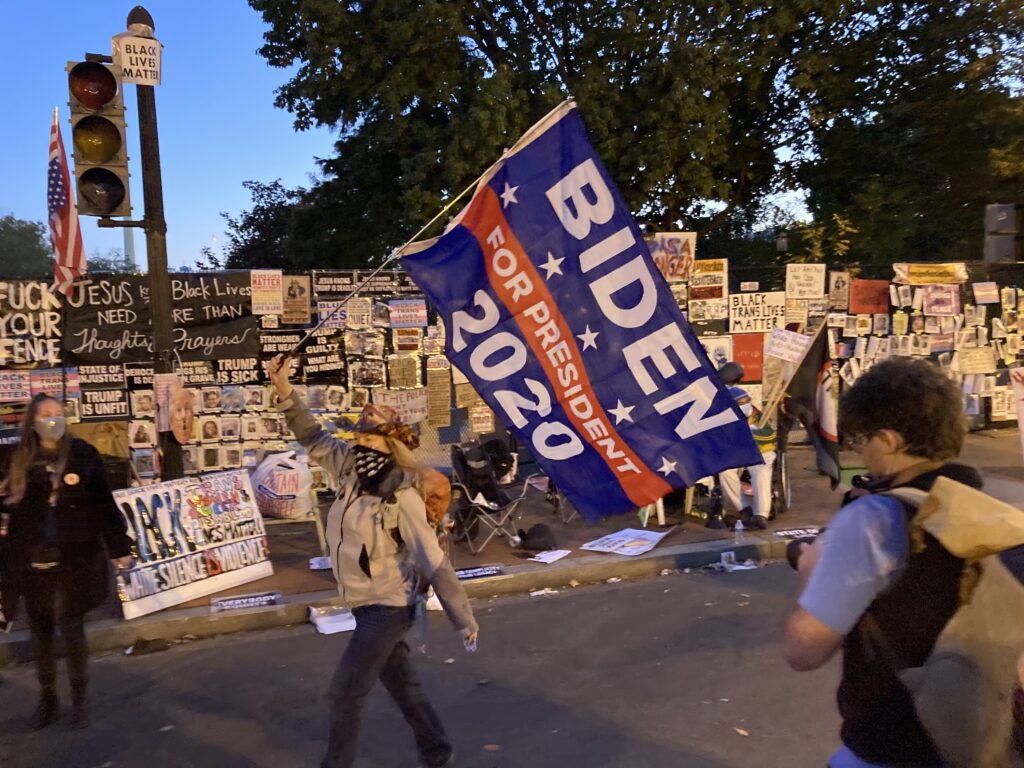

As the warm, slow dusk gradually melted away on Pennsylvania Avenue, the modest cluster of protestors blared righteous present day rap music and people began to dance. It felt like an optimistic spring night in early November. Walking away from what now seems like an unapproachable American presidential palace, I actually felt a tepid sense of optimism. I imagined a future scenario where Americans could travel to places besides Mexico and Macedonia or Tunisia and Turkey. I imagined not having to listen to an SDF commander if I, as an American, saw something resembling al-Assad in Trump.

After all the WH zone excitement that was nothing of the violent urban, Democrat-enabled mobs the president foretold, I met up with Ian Birrell, a British columnist I had met in Syria last year. He told me of his electoral adventures in Portland and West Virginia while I mentioned mine in Brooklyn and Delaware. It was one of those fleeting, collegial get togethers you wish could go on indefinitely.

The next stop on this impromptu, ballot-riddled carnival ride was Charlottesville, Virginia, a place name synonymous with the darkest hours of a grim four years. It was on the way to Tennessee–my ultimate destination–and I’d never been there before. On the surface, C-ville is a pleasant looking college town hosting the University of Virginia campus in a sea of red brick and sun rays. Some three years ago, the city hosted a loathsome event calling itself the “Unite the Right” rally in which racists, euphemistically dubbed “white nationalists” all too often by media outlets, staged a gathering centred upon a highly controversial statue of Robert E. Lee. I was in Iraq at the time this took place and so only heard about the Trump soundbites equivocating people on both sides. As I drive around the United States this year, I’ve made a point to explore the geography and symbols that illustrate the domestic news cycle in each place I travel through.

©2020 Derek Henry Flood

After all was said and done I arrived in Chattanooga where my relative Peter McAloon once fought and died for the Union fighting against Lee’s confederates in the Battle of Missionary Ridge. Once here I nearly collapsed from sheer exhaustion. A pandemic in a divided country I cannot quite leave. Yet it is home.

©2020 Derek Henry Flood